-

Vijay Fafat

- Published on

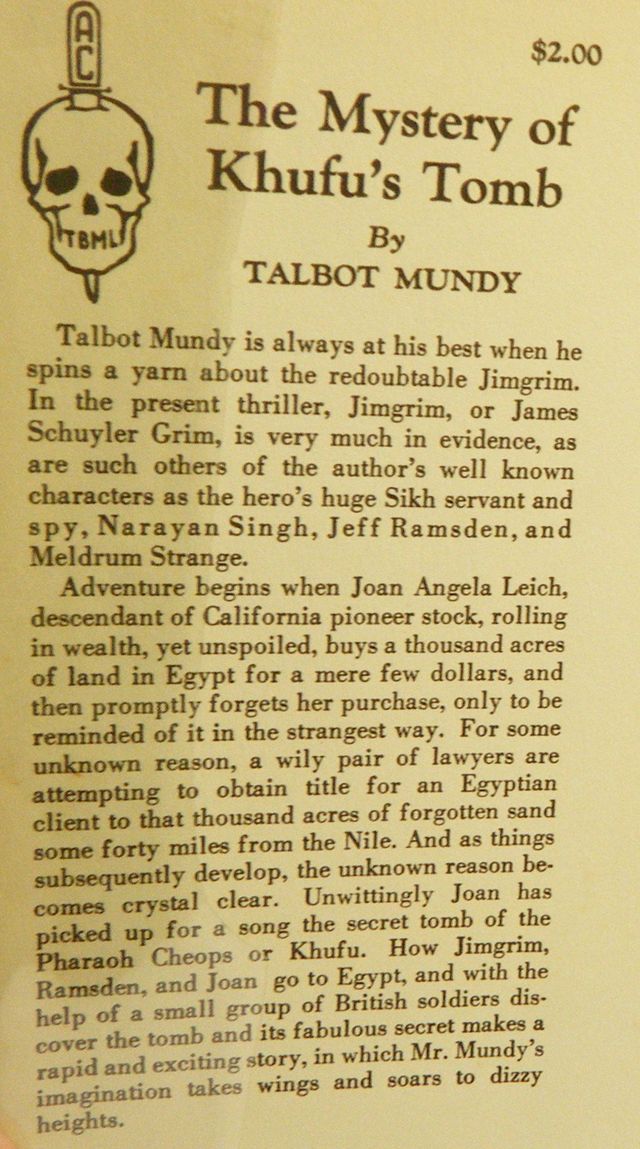

A rapid-read, reasonably entertaining novel about the real location of the Pharaoh Khufu’s (Cheops) tomb and the fabulous treasury buried therein. An old, Chinese mathematician spends decades decoding the mathematical information encoded in the construction of the Pyramid of Cheops to pinpoint the burial site of Khufu (and as a true, platonic mathematician,

“He was really only interested in the pyramid. The treasure did not attract him; what gave him exquisite delight was seeing the proof that his deductions were correct. He was too old to care for money, or too wise”

and

“[he was] much more delighted with his mathematical solution and with our bewilderment than with any thought about the value of the gold”).

General intrigue follows with an altruistic ending that the recovered treasure is to be used for the general good of the entire world.

Some quotables from the story:

“To Chu Chi Ying mathematics were religion. From the moment the little old man started figuring, and interpreting the figures, he felt himself in touch with the Infinite, and was happy” […]

“[Mathematics is the] Business of think, not guess! You know tligonometly? You know tliangulation? You know what base is? So. Look, see.”

“Mathlematics no can lie,” he answered. “You no savvy. Me savvy.”

“He was obsessed by mathematics; but, according, to him, as I understood his explanations, music and mathematics are the interpretation of law that governs the whole universe, and he who understands them owns the key to everything.

“To him, the Pyramid expressed - by means of some abstruse relation between the number of courses of stone and the height and weight of the finished building - not only the number of ingots of gold and silver that Khufu caused to be buried with him in his tomb, but their exact dimensions, purity or fineness, and the order of their arrangement underground.”

“Chu Chi Ying’s theory was this: There were men in the days when the Pyramid was built who knew Knowledge. Abstract knowledge. And abstract knowledge was their notion of the after-life and what we call heaven. Therefore, the attainment of abstract knowledge meant eternal life. But—and here was the rub, as I understood it—abstract knowledge could not be understood unless first concretely expressed in some way. In other words, he who believed he had attained to abstract knowledge had to prove it, and to leave his proof for others to follow if they could. So the Pyramid was an effort on the part of old King Khufu to express concretely the sum total of the abstract knowledge that had been taught to him by the sages of his day…”

“He went into a maze of calculations then that would baffle an astronomer who hadn’t tables to fall back on. Chu Chi Ying used never a note, set down no figures, hesitated not one second, but reeled off—in English, mind you—numbers running into billions, pointing with the long nail of his left forefinger to the various details of the Pyramid’s construction as he dealt with them mathematically, one by one. He calculated for an hour. He dragged in the precession of the equinoxes and law of gravity, the speed of light, and the mean distance between the earth and sun, and related all that-in some inscrutable fashion that seemed plausible while he was doing it—to the inside measurements of the empty granite sarcophagus—so called—that was all they ever found in the Pyramid when Al Mahmoun’s men broke in, A.D. 800. And the long and short of all that was, as he announced triumphantly at the conclusion, that the base of the Pyramid on the side opposed to the Sphinx is the base of a theoretical triangle, whose apex falls exactly on the opening into Khufu’s real tomb!”