-

Vijay Fafat

- Published on

A very touching story full of pathos, quite reflective of the Victorian era ethos in the mid-nineteenth century. The writing is high-grade, though math content itself is non-existent, since the story is about a mathematician, his personality, and his sacrifices and not about mathematics itself. While a summary appears below, the true effect is in the reading of the full story.

Clement Griffin was born a commoner, someone who

“sprang from that rude mass which is the foundation stone of society, but from whose rough, unformed depths, many a pure marble fragment has been brought to light; and doubtless there might be many more, if some skilful sculptor’s hand were found to breathe life and beauty into the shapeless mass.”.

His conditions kept him a mere

“master of writing and arithmetic in the provincial grammar-school”, (even though) “this man was at once a mathematician, a philosopher, a mechanist of the most ingenious kind, an astronomer, acquainted with nearly all the abstract sciences, and had pursued these various acquirements entirely unaided, save by the force of his own powerful mind. From both, poverty and choice, Clement was a Pythagorean, and would pore over mathematical and astronomical lore, which he followed as far as the written science of the times permitted. When he could go no farther on the track of others, he calculated and made discoveries for himself.”

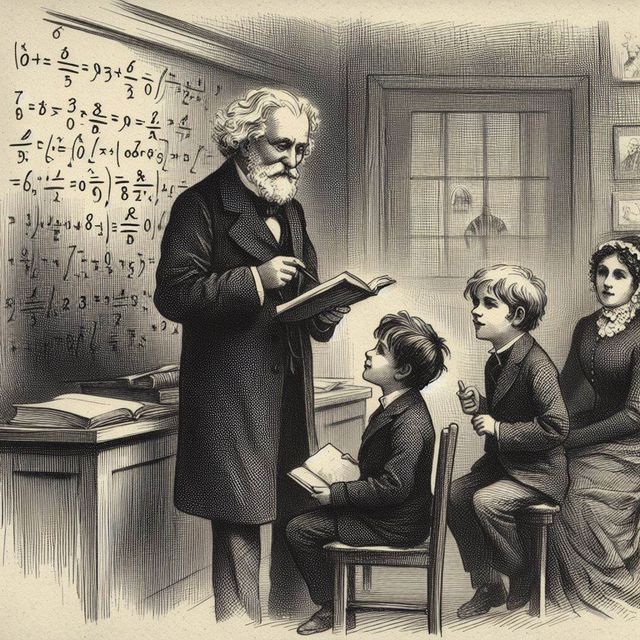

Clement was not a misogynist but he could never understand or be comfortable with a woman. He “had almost a terror of the visible poetry of the world - woman.”. In his innocent way, he got attracted to a young school girl, Agnes Martindale, who later becomes his student. The one-sided love grew but never found overt expression. Agnes got married and moved away from the village. Twenty years went by, during which time Clement invented many things but remained poor while others got rich from his efforts. Chance brought a widowed, penurious Agnes back into Clement’s life, along with her 2 children, Robert and Charles. Agnes told him that Robert had learnt all the mathematical definitions Clement had taught Agnes all those years ago and which Agnes had fondly saved as a treasure. That brought Clement one of the very few moments of joy he had experienced in life.

Clement then tutored the children for years, sacrificing his last cherished possessions of mathematical books to help pay for their education. Particularly the older son, Robert, had a strong penchant for mathematics and Clement set about to make him into “a first rate mathematician”. By the end of it, Agnes had moved back to London where Robert had found employment as a mathematical instrument-maker, thanks to Clement’s referral. She never got to know of Clement’s feelings of love or of all the sacrifices he had made. The old mathematician died penniless on the streets, with just the copy of Bible which Agnes had given him as a child in his possession…

As the final paragraph summarizes so poignantly a lesson in humility for all:

“No admiring disciple has ever raised a stone above this unknown philosopher. He foretold, half a century ago, that men would journey by steam; now, the lightning-like railway passes within sight of his grave. He spent years in perfecting a mechanical invention: its wheels now whirl in a roar in a manufactory not two hundred yards from the green pillow where the brain which first conceived their uses is peacefully mingling with the dust. He first declared that the human mind and character were faithfully portrayed in the human head as in a map: not long since, in the little town where his wanderings ended for ever, a phrenologist - a learned man, too - lectured to crowded audiences on the new science. The sage - the philosopher - the devoted follower of science - has passed away and left no memory - no, not even a name written on a churchyard stone. Yet what matters it? The great men of earth are those who have done most good to that world which may never know or utter their names. But,

“The seeds of truth they sow are sacred seeds,

And bear their righteous fruits for general weal

When sleeps the husbandman.”