-

Vijay Fafat

- Published on

A short, heart-breaking tale which captures the heartache which, not so uncommonly, befalls a researcher who makes a monumental discovery, only to find that independently and unbeknownst to her, someone else had already found it earlier…

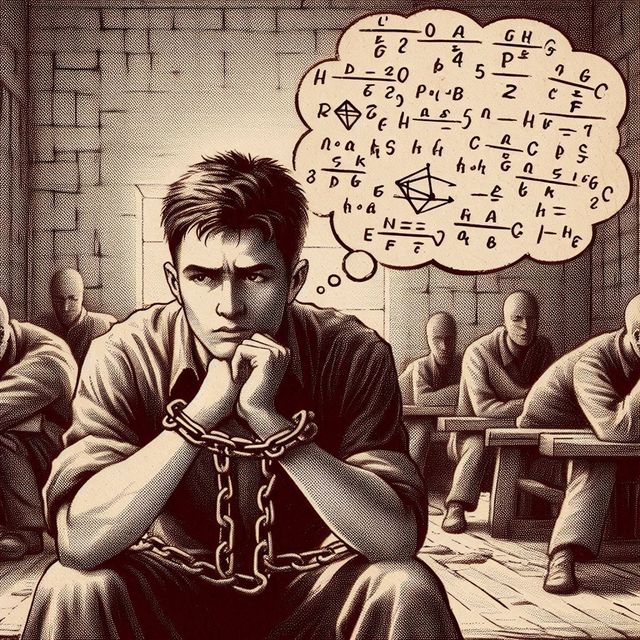

Donald was a frail but brilliant student, destined for greatness. True to expectations of his colleagues, he had obtained scholarships for studies in mathematics, first at Oxford, then at Yale. But then, the World War II intervened and Donald enlisted to join the Infantry Regiment. The narrator saw him sailing off to India for the war. Unfortunately, after just a day’s fight in Singapore, he became a PoW with the Japanese, who shipped him off to the grueling conditions, working on building the Burma-Siam railroad.

Confounding all expectations, Donald endured all of the hardship and cruel conditions imposed on the PoWs well, even improving in health in the process… Presumably, this was because his mind was singularly focused on solving a mathematical problem

“Neither the Japanese nor his follow-prisoners could ever discover the source of his strength. He suffered from the broiling sun no less than did his companions; even more than most he was unfitted for continuous physical drudgery , and he shrank from the brutalities to which all were subjected. But all the time on the blackboard of his mind he worked out mathematical problems, closing out pain, humiliation, and tragedy.”

Does this not remind one of Karl Schwarzschild, the Physicist who volunteered for World War 1 despite being above 40, and producing brilliant mathematical calculations on General Relativity while fighting on the Russian front?

And then,

“Donald at last came to that glorious moment in January 1944, when he realised that his; thought-processes had arrived at a triumphant - and, to a scholar, an earth-shaking conclusion—when he knew that he had produced and proved beyond dispute a theory unknown to all his mathematician predecessors.”

After the war was over, Donald rushed to meet a leading mathematician at Oxford, Prof. A B Wynyard. Wynyard was an authority in the field of Donald’s discovery and immediately saw that Donald had produced a deep, fundamental result. He offered Donald a stiff drink of whisky and a chair to sit down before telling him:

“ ‘Drink up! It’s superb, this theory of yours. magnificent, beautiful. But…’, and now, it was Wynyard who was stumbling over his words, ‘but I have it here somewhere … In 1942 or perhaps in 1943 it was… Professor Svenson… you know… Albert Svenson at Uppsala … Svenson who published the same theory… in my opinion mare than a theory, it’s incontrovertible… and put it in an American iournal. Now which journal was it? I know I have it here somewhere…’ ”

After that, Donald did not receive the accolades for which he was destined. He lived a comfortable life in America as a professor, having written a masterpiece mathematics textbook for college and university students earning handsome royalties. However, as the narrator ends the story, something remains amiss… :

“But sometimes, as I sit with him listening to Sibelius or Grieg, I think that I see something behind his eyes. Though I cannot see or comprehend it, I know that he is chalking hieroglyphics on the blackboard of mind, and I cannot be certain if it is sweat or tears that blind him to that wondrous realisation of Q.E.D.”