-

Vijay Fafat

- Published on

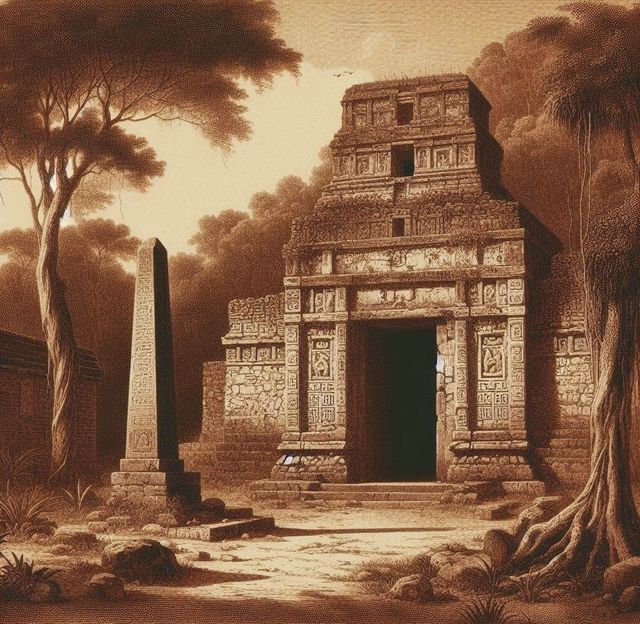

A cute, poetically-written story set in the Yucatan, where Ethel, her cousin, Tom, and Tom’s college friend, Whitman, went looking at the ruins of an ancient Aztec “Temple of Huitzilopochtli”.

Whitman was a young man quite heavily into mathematics, though according to Tom, “mathematics was never kind to him”. Whitman had always avoided women and maintained that women were “poor mathematicians” and that “mathematics seemed for men, and poetry for women”. But he fell in love at the first sight of Ethel, without knowing how to attract her attention. As to Ethel:

“she was a remarkable girl and had sailed through Vassar in a halo of mathematical glory, with the special commendation of Maria Mitchell ; and he had a soft place in his heart for any one who courted the mathematics.”

The temple they were visiting had a legend surrounding it. As Ethel described it:

“You wanted to know about those Edgar Allan Poe human sacrifices they used to have. Here ’s the story. People from all around the country used to go there, and a good many of course were of the very pious kind, who hung around in the temple, worshipping like sixty till all of a sudden they found that the water was beginning to rise. This used to take place about supper-time, and by that time a big obelisk outside had thrown a shadow clear across the doorway. Well, this shadow was a consecrated shadow — some sun-god business — and to cross it was a horrible sacrilege. But the people inside did n’t know anything about the shadow, ten to one; and if they did, it was n’t any use; they had stayed so late. Out they would rush, and the priests tended to the rest. In that way they satisfied Maya scruples and Aztec requirements.”

When they reach the ruins, Ethel refused to go inside and explore the dark interiors while Tom was all gung-ho about pulling an Indiana Jones. So they agreed that Tom would go in alone but come back before the shadow of the obelisk crossed the doorway, even though none of them believed the ancient priesthood had survived to modern times to implement the grisly legend. To calculate the maximum time for return, Tom suggested that Ethel do some mathematical calculations and show to Whitman the error in his thoughts:

“I’ll tell you,” said Tom, you work it out by mathematics ; that will be sport. Make Ethel do it. There, my dear, is a chance to show that men are poets, and women mathematicians. She started at having her words thrown up at her so soon, and colored deeply, but she felt that the reputation of her sex rested upon her. She threw her head back and a little to one side, defiantly, as women will when combative, and accepted the challenge. Out came Whitman’s long lead-pencil and mathematical tables, and Tom brought forth a dilapidated note-book. Whitman’s omnipresent tape-measure on the end of a stick showed the height of the pillar above the terrace to be fifteen feet. How long would it take the shadow to block a doorway forty nine feet distant? This was child’s play for a Vassar girl. Find the angle which the sun made with the summit of the pillar ; divide by ninety degrees, and multiply the number of hours between noon and sunset by this proper fraction. Now the sun was setting at forty minutes past five to-night; so there were all the data.

Don’t forget the refraction,” said Whitman, with a laugh. Now refraction would have altered the result some three minutes, but Miss Ethel was thrown into consternation ; for all she knew, it might make the difference of an hour. She bit thoughtfully at the pencil, and the point broke. Whitman sharpened it for her. Just then she saw a table of refraction coefficients ; thank Heaven, she knew how to use them ! It was all on page twenty-seven ; she remembered it all by heart. The amount of mathematics a young lady can get by rote is amazing. She uttered a sigh of relief; she realized now how frightened she had been, for the figures gyrated in all directions, and ciphers and decimal points kept disappearing; she must be careful, or she would get something down wrong. Whitman should never know how near he had come to catching her, and the mathematical reputation of her sex was preserved in its integrity, so far as she was concerned. There, the problem was done ; at 5.01 P. M., precisely, the shadow would reach the doorway. Tom was to allow five minutes lee-way, and come out at 4.56

Well, as it so happened – quite unfortunate for the reputation of women with respect to mathematics, Ethel made an error:

“It was her turn, now, to relieve the monotony. By the way, what do you think of that for trigonometry ? ” and she gayly handed him the paper containing her computations of the afternoon. He thought she seemed a little ill at ease, as if she began to doubt her work, in the awesome quiet of the woods. He smiled, and glanced at the figures carelessly, then started, and began to figure rapidly. Silence, deep and unbroken. “ Well, what ’s the matter, sir ? ” she broke in, impatiently. w Why, the refraction coefficient of vacuum to air is 1.00029, not 1.0294, and you bring the answer out twenty-six minutes too high. Taking out the five minutes, Tom will come out twenty-one minutes too late.””

Right around this realization came a further revelation – the old priesthood was alive and well, waiting for its victim at the top of the hill…. And Whitman realized that to save Tom, he had to either kill the priest, stop the dangerous trapping condition in the temple, or make the obelisk’s shadow not fall by the temple entrance.

“Why don’t you save him ? ” cried Ethel ; and there was a fine light in her eyes, and her hands were clenched now. Whitman felt that any other girl would have fainted long ago, and a wave of admiration swept over him.

“Oh, if you were only a man, and not a fossil ” — it sounded ludicrous at such a time —1 am going up myself. Poor old Tom!” He had the presence of mind to seize her bridle rein. Parabolas, hyperbolas, — what not darted through his head, poor aids at such a time. After all, calculus was a small thing to know when human life hung in the balance and quick wit might tip the scale. He knew now that the good opinion of this young lady was not so undesirable. He would give a good deal for it at this moment.”

And from there, Whitman figured out that it might not be too difficult to topple over the Obelisk, if still at considerable risk to himself. Which he did, saving the day and winning Ethel’s heart…

As was characteristic of the fine prose-writing of the era, the author did good work of setting up the mood, describing the Yucatan afternoon, the impending doom, and managed to sprinkle some subtle wit throughout. Quite enjoyable.

A few more excerpts:

“Whitman vacantly off sat toward on the veranda dull glow and looked in the west. Twilight in Yucatan is no time to discuss mathematics, and, with a young lady in a great armchair only a few feet away, it is sacrilege. Still, that was the subject of the conversation.

“How absurd ! So you really think women are poor mathematicians?” It was a hard question, but Whitman was not the man to flinch.”

“It was no use; it wasn’t possible to get to sleep that way ; and, besides, [in his waking dream] there was a sheep who proved to be Montezuma, last emperor of the Aztecs ; and he wished to extract his young friend’s heart in the good old Aztec fashion ; for as far as he — Montezuma— could see, he had no use for it. Then Miss Ethel — for it was she — said the square on the hypotenuse was a circle — It was six when he awoke, and the horses were ready.”

“Hope not, William. She likes you immensely, only you ’re such an old mathematical fossil. To be grave, here’s a piece of sound advice. Be a fossil all you want, only, when the time comes to act don’t stand like a stump as most fossils do. Otherwise — good-by to the ladies. Really, unless you sober down from your sines and cosines, she can never…”

“She isn’t old, you know; why, only— well, log 2.301030, which is the same as not telling you.”